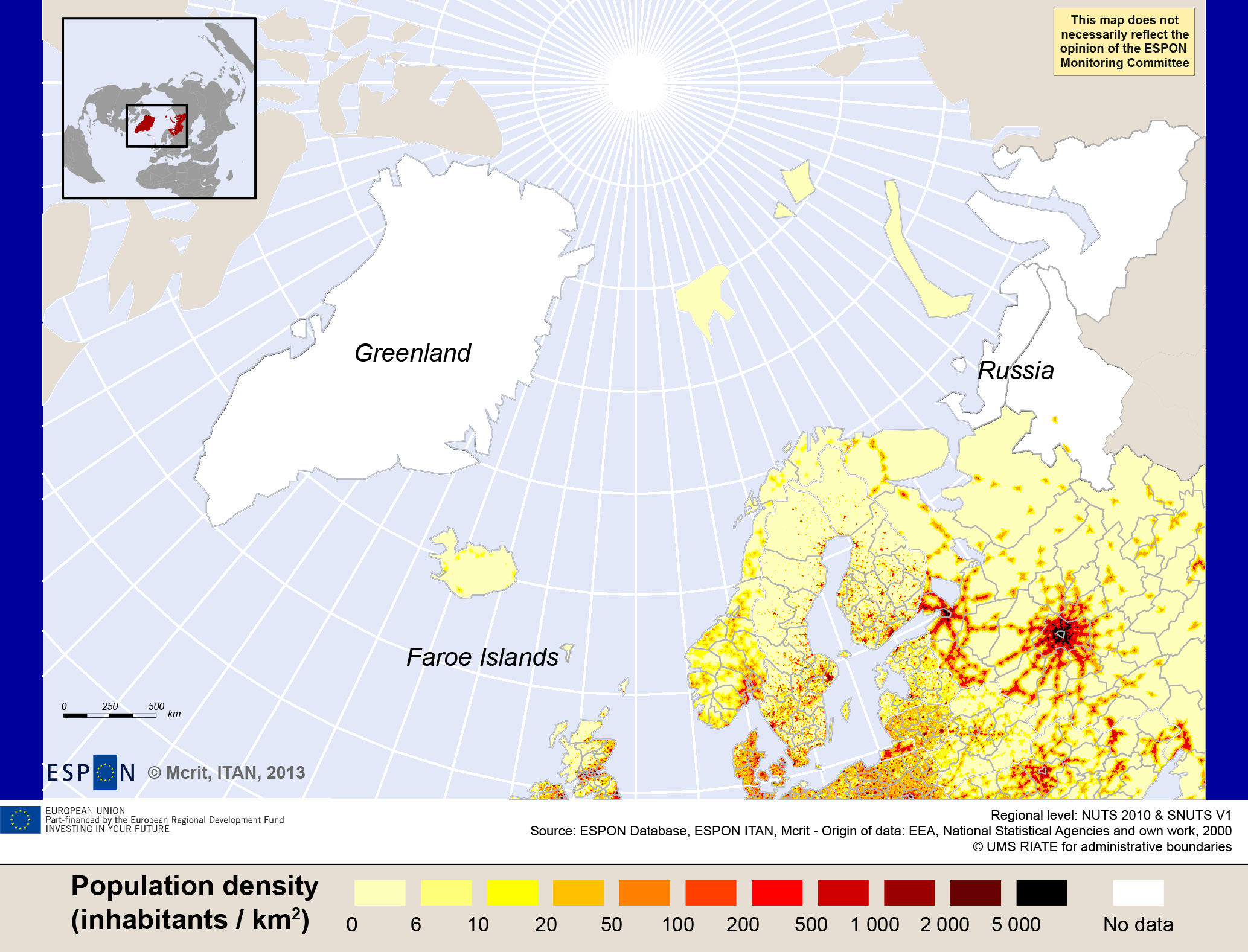

The Northern Neighbourhood (which includes two autonomous regions, Greenland and the Faroe Islands) shows very low population compared to both the other Neighbouring regions and to the EU-27, although its annual population growth is similar to EU-27. Population density is extremely low, with isolated “hot spots” around regional centres and further south radiating from the transport nodes of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Urban settlements are highly dispersed in the Northern Neighbourhood. Most of them emerged in areas that are rich in natural resources and due to the development of resource extraction industries. The Northern Neighbourhood, unlike what might be expected, is highly “urbanised”: more than 90% of the population of Greenland and Murmansk oblast live in urban centres and about 80-90% of Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Oblast live in urban areas. This is mainly due to difficult climatic conditions, low accessibility of the region and limited access to services (e.g. health care and education). Thus urban centres are becoming more attractive to live in.

Reflecting the dispersed settlement pattern, transport networks are much less dense than in the EU-27 or even in the Nordic countries. There are few main railways, no large airports, the large sea port in Murmansk is of strategic importance to Russia as a year-round ice-free port. There are also no motorways and a limited number of main roads. Although Greenland data is not available, road system is very small (a few hundred kilometres) and most travel between settlements is by plane, boat or dogsled.

Due to climate change and melting ice, the possibilities of increased transport with the opening of the North-West and North-East passages will facilitate greater exploitation of oil and gas resources, thus making the Arctic an important geopolitical territory for both Europe and the rest of the world.

Despite a harsh climate and dispersed settlement pattern, mobility is high. People are moving towards regional centres and larger urban nodes within the region but also abroad, to the more populated areas in the West, East and South of the North Neighbourhood. A remarkable share of the migration is related to limited labour possibilities in the home regions and in the case of more rural and peripheral regions in relation to education possibilities. Also fly in-fly out phenomenon is common in some settlements, especially in those where the economic structure is heavily concentrated on natural resource exploitation.

As a social indicator, gender balance nicely shows some of the challenges and territorial specificities of the area. The male population of working age is slightly higher in the whole Northern Neighbourhood, particularly in Greenland and Murmanskaya oblast. This can be explained by the development of strongly male-dominant industries there –oil and gas exploration fields, mining activities, military bases, construction and forestry. Employment possibilities for females are quite limited and available mainly in larger urban centres.

When it comes to the total gender balance including all age groups, the proportion of females is significantly higher in all areas of the Northern Neighbourhood, except for Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Overall, adult males tend to have higher death rates than females. This trend is exacerbated due to tough work environment in the industry sector which exposes many workers to health hazards, but also harsh climate, low quality of housing, inconsistent and poor quality of health care and excessive consumption of alcohol among male population. In the case of Greenland, the dominance of male population can be explained by high outmigration of female population from the country. The gender unbalance calls for the diversification of the economy in order to provide workplaces for everyone and keep people in the Northern Neighbourhood.

Policy orientations for territorial issues and cooperation

There are discussions whether the Arctic Council as the main governance structure, is resistant enough to accommodate current changes. With the possibilities to exploit the region’s vast natural resources, it is now up to discussion if the Council is still to be the predominant inter-governmental forum or if it should be succeeded by other forms of governance. The discussion on the future of Arctic governance is focused on whether to create new structures and regulatory frameworks, or build on already existing multinational frameworks. In order to attract international investment for energy and mining projects, a clear legal framework will be needed as it would be central to the management of fisheries, oil and gas exploration as well as to the national and energy security issues. It would also be central to the operation of commercial shipping and the management of possible accidents that may occur beyond the national boundaries, along with any other potential activities that may arise.

As commercial interests will increase dramatically, it is integral that all the actors consider the benefits for the entire Northern Neighbourhood in a cooperative environment and not only see their self-interest. It is of utmost importance that the notion of “common goods” be largely applied to this Neighbourhood’s resources, and pave the way for modern post-national governance. In this more and more strategic Neighbourhood, the notion of “regionalisation” (increasing output, actual and potential flows at the scale of the Neighbourhood) might be an excellent driver for such better “regionalism” (regional agreements). Countries outside of the Arctic region are competing for access to a type of territorial capital that has traditionally been a common good, rather than a strict jurisdictional territory. Thus, a Neighbourhood’s common legal framework will be needed, for instance so as to attract international investment in a sustainable way and turn regional threats into opportunities.

The EU has a special Arctic Strategy which is built around three main policy objectives: protecting and preserving the Arctic environment, promoting sustainable use of resources and international cooperation. The EU also has applied for permanent observer status in the Arctic Council. Thus there are strong strategic and geopolitical visions of the European links with the region. However EU Cohesion policy instruments could be further extended to pay specific attention to the territorial ramifications of increased exploitation of the territorial capital within the area. A difficulty comes out from the fact that the European part of the Northern Neighbourhood belongs to various European Territorial Cooperation programmes: the Cross Border Cooperation (ENPI CBC), the Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme 2014-2020 for the Westnorden, the Northern Dimension policy (which is an important venue for dialogue with the Russian neighbour). This calls for a more unified and ambitious EU strategy on this Neighbourhood.